In basic economic principles, risk is directly proportional to return. The higher the risk taken by an entity, the higher the expected profit. In the context of transfer pricing, risk analysis is not merely a supplementary formality, but a vital component of Functional, Asset, and Risk (FAR) Analysis that determines how large a "slice" of profit an entity in a multinational group is entitled to receive.

Global guidelines such as the OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines 2022 and UN Transfer Pricing Manual 2021, as well as local regulations in Indonesia (PMK 172/2023), Malaysia (TP Guidelines 2024), and Singapore (IRAS TPG 8th Edition), have now shifted from merely looking at risk allocation on paper (contracts) to testing the substance regarding who actually controls (control) that risk.

Risk, in the context of transfer pricing, is defined as the effect of uncertainty on business objectives. Every business decision—from launching a new product to granting credit to customers—contains uncertainty about whether the actual result will accord with expectations.

Based on Indonesian Tax Audit Guidelines (PER-22/PJ/2013) and Malaysian guidelines, risks that must be identified include:

OECD and UN recommend a six-step framework for analyzing risk, which is also adopted in principle by tax authorities in Southeast Asia:

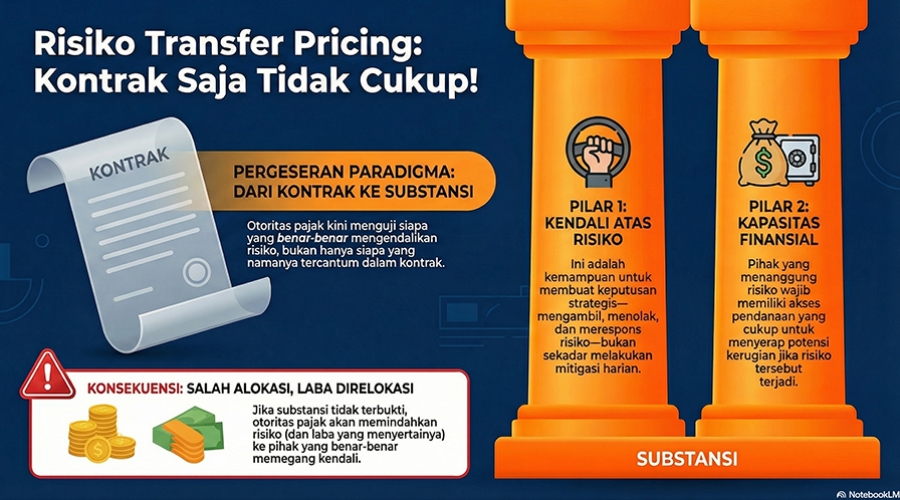

This is the core of the post-BEPS (Base Erosion and Profit Shifting) transfer pricing paradigm. Just because a contract states "PT A assumes the risk of R&D failure", does not mean the tax authority will accept it.

According to Malaysia Transfer Pricing Guidelines 2024 and OECD, for an entity to be considered as assuming risk, it must have "control". Control is defined as the ability to make decisions to take on, lay off, or decline opportunities containing risk, as well as decisions on how to respond to that risk.

In Singapore, IRAS affirms that if risk allocation in the contract differs from economic substance (who makes decisions), then economic substance prevails.

The entity assuming risk must have the financial capacity to bear the negative consequences if the risk actually materializes. This capacity is defined as access to funding. If an entity does not have the financial capacity to bear losses, the risk will be reallocated to the party possessing that capacity.

In PMK 172 of 2023, Indonesia affirms that risk analysis is an inseparable part of functional analysis. If the Taxpayer cannot prove that they actually control the risk, then the risk can be disregarded or reallocated.

The Malaysia Guidelines 2024 provide an example: If a company provides a loan without security where no independent party would do so due to high risk, the tax authority (DGIR) can disregard or recharacterize the transaction.

If an entity only provides funds but does not control the research risk, the entity is considered a "Cash Box". According to OECD and UN, such an entity is only entitled to a risk-free return on the funds lent.

In the current tax landscape, "Paper" (Contracts) is no longer an absolute shield. Risk in transfer pricing is about the substance of decision making. For Taxpayers in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore, it is crucial to ensure that the entity recorded as assuming risk in the TP Doc truly possesses (1) competent directors/management to take decisions, and (2) a strong balance sheet to absorb losses. Without these two things, your risk allocation is vulnerable to correction.

Is My Company Required to Create a Transfer Pricing Document?