In the legal realm, particularly in tax dispute resolution at the Tax Court, the principle of evidence plays a vital role in achieving justice. One legal maxim that frequently serves as a fundamental basis in court proceedings is "Affirmantis est probare." Literally, this maxim translates to "he who affirms must prove".

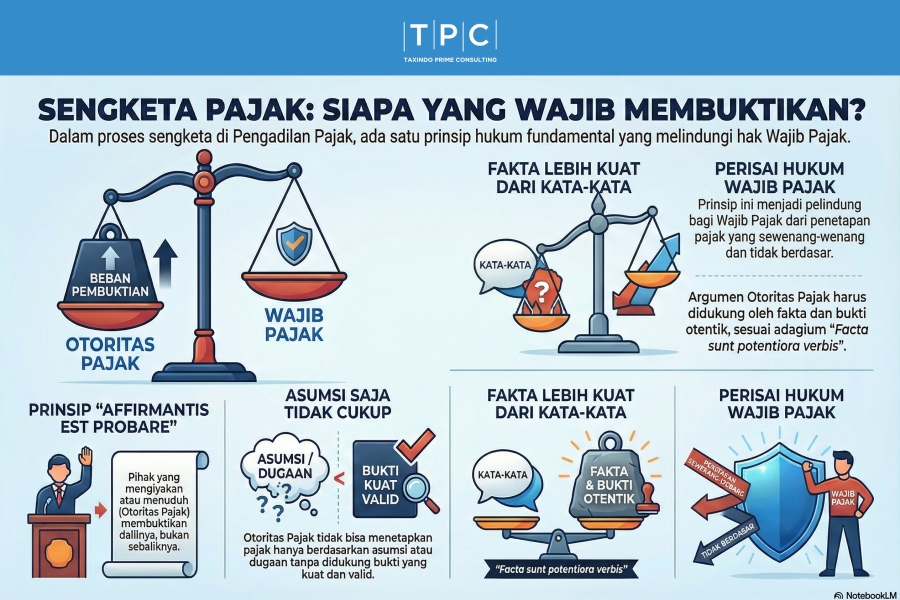

This principle asserts that the burden of proof lies with the party making a positive claim or allegation. In the context of tax disputes, this means that if the Tax Authority (the Appellee) asserts that a Taxpayer has unreported income or that a transaction is unreasonable, it is the Tax Authority that is obligated to provide evidence for that accusation, not the Taxpayer who must prove otherwise.

The application of Affirmantis est probare is closely tied to the Judges' pursuit of material truth. According to the Elucidation of Article 76 of Law Number 14 of 2002 concerning the Tax Court, Judges strive to determine what must be proved, the burden of proof, and a fair assessment for the parties involved. This principle prevents tax assessments based merely on assumptions or conjectures without a strong basis.

In practice, this maxim is often paired with the adagium "Facta sunt potentiora verbis," which means "deeds or facts are more powerful than words". This implies that mere narratives or arguments from the tax authority are insufficient to sustain a fiscal correction if they are not supported by facts and authentic evidence.

A concrete example of this principle's application can be seen in appeal disputes between Taxpayers (such as in the PT Het Waren Huis case) and the Director General of Taxes. In such disputes, the Tax Authority often makes positive corrections by deeming service payments to affiliated parties as non-existent and re-characterizing them as constructive dividends.

In their defense, the Appellant (Taxpayer) invokes the Affirmantis est probare principle. The Appellant argues that since the Appellee "affirms" or alleges that the transaction does not exist, the Appellee must prove this non-existence with valid evidence, rather than relying on assumptions.

The Tax Authority is not permitted to shift the burden of proof to the Taxpayer to prove the absence of a tax object (a negative), as this contradicts the principle of negativa non sunt probanda (negatives need not be proved).

When the Tax Authority fails to prove its allegation—for instance, by failing to present adequate functional, asset, and risk analysis or by ignoring transfer pricing documentation presented by the Taxpayer—the correction becomes legally groundless. The Tax Court Judges, with their authority to assess evidence (Article 78 of the Tax Court Law), will overturn the correction if the Tax Authority fails to meet its burden of proof.

The Affirmantis est probare adagium is not merely a legal theory; it serves as a shield for Taxpayers against arbitrary tax assessments. Conversely, it demands professionalism from the Tax Authority to always base fiscal corrections on competent and valid evidence, not merely on suspicion. This balance is essential for realizing justice and legal certainty within the Indonesian tax system.